For hundreds of years, the Turkana pastoralists of northern Kenya have adopted the water. Households as soon as moved about 15 instances a 12 months searching for watering holes for his or her cows, donkeys, camels, goats and sheep.

However the Turkana folks’s seasonal lifestyle has develop into precarious in latest a long time. With drought and ongoing combating throughout the area, many ladies and youngsters keep put whereas males roam the panorama — usually at their very own peril. Violence has pressured many households to flee for his or her lives at a second’s discover. Separated from their livestock, these households eke out a dwelling alongside the sides of cities or bide their time in displacement camps ringed by tightly woven fencing.

Friendships constructed on the trade of livestock additionally disintegrate. “When nobody has any animals, how can we assist each other?” a Turkana lady requested anthropologist Ivy Pike, who has labored within the area for 25 years, throughout an interview.

The struggling inside these communities is profound, says Pike, of the College of Arizona in Tucson. Unable to securely comb the panorama for medicinal vegetation, resembling herbs to stem postpartum bleeding or curb fevers in youngsters, girls discover it laborious to meet their function as nurturers. Males’s identities, in the meantime, are sometimes so certain up in proudly owning livestock that the Turkana language has a phrase to explain a person with out animals — ekebotonit.

“The loneliness of getting no animals holds a specific place of misery that transcends the meals and livelihood that livestock provide,” Pike and a colleague wrote in 2020 in Transcultural Psychiatry. “An ekebotonit … not solely loses his sense of function and the companionship herds provide, however in keeping with the Turkana, turns into erased — a person with no say in society.”

These experiences of loneliness amongst many Turkana folks reveal how the sensation defies easy characterization — it’s greater than social disconnection. That complexity is seen in cultures worldwide. In a research executed in the USA through the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, as an illustration, many respondents attributed their loneliness to a number of components that left them feeling disconnected. One lady missed going to the grocery retailer, anthropologist Michelle Parsons of Northern Arizona College in Flagstaff reported in 2022 in SSM-Psychological Well being. One other lady longed to browse the stacks on the library, a sometimes solitary exercise.

Efforts to broaden the definition of loneliness to incorporate a sense of disconnect from animals, locations, habits, rituals and even the climate have been gaining momentum throughout the social sciences. In October 2020, as an illustration, Parsons coauthored the introduction to a particular difficulty on the anthropology of loneliness in Transcultural Psychiatry.

Getting a deal with on the constituents of loneliness — and its flip facet, belonging — isn’t just an educational pursuit; it’s a matter of public well being, analysis suggests. In a Could advisory, U.S. Surgeon Basic Vivek Murthy declared loneliness a public well being epidemic, citing findings from quite a few research: Loneliness seems to extend an individual’s threat of coronary heart illness by 29 p.c and threat of stroke by 32 p.c. In older adults, persistent loneliness is related to a 50 p.c improve within the threat of creating dementia. Social isolation can improve the chance for untimely demise by 29 p.c.

Broadening ideas of loneliness will help broaden the toolkit of doable interventions, Parsons says.

Tethering folks to the broader world may even assist folks acknowledge and tackle local weather change, suggests geographer Sarah Wright of the College of Newcastle in Callaghan, Australia. This course of begins, she says, by “constructing intentional relationships with greater than human beings.”

Historic types of belonging

To grasp belonging and by extension loneliness, Wright has seemed to Indigenous communities. Although these communities span the globe and are comprised of myriad practices and languages, broadly talking, they share a perception that well-being stems from concord between folks and the planet (SN: 9/23/23, p. 14).

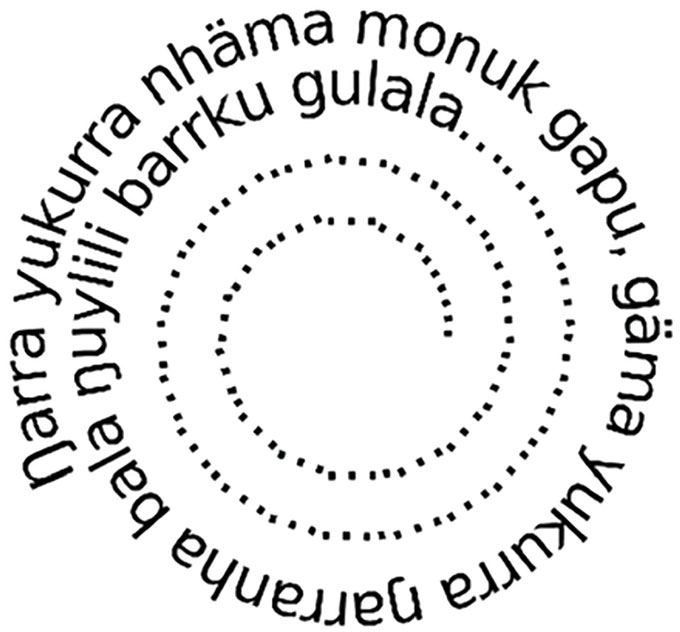

Wright and colleagues lately studied the tales the Aboriginal Yolŋu folks inform by means of ritualized songs often known as songspirals. This historic apply explores the connections amongst place, tradition, folks and the tales they inform. Wright’s group, together with members of the Yolŋu neighborhood and drawing on the work of the Homosexual’wu Group of Girls, printed an evaluation of 1 matriarch’s songspiral in 2022 in Qualitative Inquiry. Consistent with the Yolŋu world view, Bawaka Nation, the tribe’s homeland in northern Australia, is listed because the lead writer.

Whereas mendacity on her deathbed, the matriarch started singing about her place, her sense of belonging, inside a large net of human and nonhuman relationships. In accordance together with her folks’s custom, the matriarch noticed this final journey as taking her to the ocean; she envisioned herself as a whale. “I can see the saltwater carrying me, transferring along with the present; carrying me additional into the depths of the ocean, the place the muse of my bloodline lies.”

The matriarch constructed from an historic script, one which spirals outward from a unvoiced land, clarify the authors. That track at all times begins one thing like: “Originally of time somebody needed to speak for the land, it was quiet, nothingness. After which it started with the sound from deep inside the water, ‘Hmmm hmmm.’ That was the place to begin.…”

From there, the matriarch’s track strikes ahead and backward throughout generations to anchor folks within the broader arc of time, Wright says. The matriarch sings of swimming alongside her deceased grandmother; she sings of her daughters, her granddaughters and her great-granddaughters.

The track additionally anchors the Yolŋu folks to their homeland by giving voice to whale migratory patterns, key fishing grounds and bodily connections throughout the land and sea. The songspiral “maps the land from the ocean perspective,” Wright says.

The matriarch’s songspiral exhibits how for the Yolŋu folks, nonhuman relationships are as actual as relationships with people, Wright says. With such relationships, folks really feel a way of belonging on the earth. With out them, folks really feel misplaced.

Because the matriarch’s daughter Merrkiyawuy explains within the paper, if the legal guidelines of stability between folks and land, or nation, are damaged, “the spiral can come tumbling down and burst. That’s what we are saying, it’ll burst open and simply float and you’ll be like a leaf floating within the air, nothing controlling you … if that spiral is burst open, then the songs disappear.”

Shedding place — by means of migration, improvement, local weather change or another trigger — can manifest as loneliness in Indigenous communities, different analysis suggests. For example, in 1987, anthropologist Theresa O’Nell of the College of Oregon in Eugene started an 18-month research of despair among the many Salish and Pend d’Oreille peoples dwelling on the Flathead Reservation in Montana. However each time O’Nell requested folks if that they had ever been depressed, they’d invariably speak about loneliness.

“Time after time, I requested about ‘despair,’ and time after time, I used to be instructed about ‘loneliness,’ ” O’Nell recounted within the 2004 difficulty of Tradition, Drugs and Psychiatry. For example, O’Nell cited “the loneliness of an elder lamenting the lack of a track that’s now not sung.”

O’Nell attributed this loneliness to a number of causes, together with a sense of exclusion from society, an existential feeling of separation between the self and the next energy, and bereavement over shedding rituals and language. The Salish and Pend d’Oreille peoples, she noticed, didn’t see their loneliness as pathological, however as an alternative noticed it as a pure response to the erosion of their lifestyle.

“Historically oriented Indian individuals are much less vulnerable to disappointment and extra vulnerable to loneliness,” says Joseph P. Gone, a psychologist at Harvard College and a member of the Aaniiih-Gros Ventre tribal nation positioned in Montana.

If land loss is linked to loneliness, particularly in Indigenous communities, then the sensation can be anticipated to develop as local weather change wreaks havoc on folks’s ancestral lands. (SN: 3/28/20, p. 6). For example, the 2019–20 bushfires that scorched tens of millions of hectares in Australia brought about super struggling for Aboriginal communities, researchers in Australia who labored with these communities wrote in 2020 for the Dialog, a nonprofit information group: “For Aboriginal folks … who reside with the trauma of dispossession and neglect and now, the trauma of catastrophic fireplace, our grief is immeasurably completely different to that of non-Indigenous folks.”

Eager for day by day rituals

An emphasis on concord between folks and the planet seems much less incessantly in industrialized cultures, Wright says. “The truth that you possibly can have a nourishing relationship with place has been invalidated.”

However because the pandemic illuminated, even in industrialized cultures, many individuals’s sense of belonging nonetheless hinges on connections to the more-than-human world. Moderately than a connection between particular person and the panorama, although, these relationships incessantly present up between folks and elements of the constructed surroundings.

This want for relationships with the constructed surroundings comes by means of in journal entries submitted to the Pandemic Journaling Mission, Parsons says. This world initiative to assemble folks’s experiences of the historic well being disaster amassed some 22,000 entries from 1,750 folks from Could 2020 to January 2022.

“The loneliness creeps up on me. It seems out of left subject. The will to only go and hang around with associates, exit to eat, even browse stacks on the library,” wrote Denise, described as a divorced Midwestern Black lady in her 60s.

The everyday instruments psychologists use to measure loneliness in all probability miss these emotions, Parsons reported in her 2022 article in SSM-Psychological Well being. She reached that conclusion after homing in on 35 U.S. journal writers, many with a number of entries, who used phrases containing the fragments “lone” or “isolat” in at the very least one entry. The journal writers additionally crammed out a five-statement loneliness survey alongside their first entry after which each six weeks thereafter. Journal writers responded “sure,” “roughly” or “no” to statements resembling: “I miss having folks round me.” “There are many folks I can depend on when I’ve issues.” “There are sufficient folks I really feel near.”

Regardless that many respondents reported feeling lonely of their entries, they nonetheless scored low on the loneliness survey, Parsons discovered. For example, on the identical date that Taylor, described as twentyone thing, nonbinary single white particular person, wrote that that they had “by no means been extra lonely,” they scored a 0 on the loneliness survey.

Parsons attributes the discordance to limitations within the survey. The psychological survey used within the journaling venture, referred to as the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, and one other broadly used survey, the UCLA Loneliness Scale, each outline loneliness as a type of social ache introduced on by the felt absence of a social community or significant relationships.

By design, then, most loneliness surveys miss folks’s connections to locations, actions and even informal acquaintances. Within the journaling venture, folks wrote about lacking rituals and different practices, resembling birthday celebrations, holidays, spiritual providers and funerals, or lacking locations, such because the gymnasium, grocery retailer, library and associates’ homes, Parsons notes. Individuals additionally wrote about lacking on a regular basis encounters with others, the seemingly mundane interactions that may come up when folks wander their communities.

These emotions of loneliness present up in one in every of Taylor’s entries. They write: “Not solely do I miss my associates, however I additionally miss strangers. I miss the random encounters I used to have with folks on the road, in shops, at bars. I miss making a reference to somebody after which going our personal methods.”

The De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale is nice at capturing a eager for the form of deep, significant relationships that folks sometimes affiliate with loneliness, but it surely misses different types of loneliness, Parsons says. “It’s not selecting up place in any respect. It’s not selecting up practices.”

Increasing the loneliness toolkit

Together with the constructed surroundings in assessments of loneliness just isn’t but frequent. However architects, whose commerce rests on understanding how folks transfer about their communities, usually intuitively take into consideration how the design of the bodily surroundings can worsen emotions of isolation or foster belonging.

“We often consider loneliness as a singular situational, social or psychological expertise of being indifferent from place, domicile, or different human beings,” reads the opening line of the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa’s chapter within the 2021 e-book of essays and lectures Loneliness and the Constructed Surroundings.

Many architects, together with Pallasmaa, have discovered inspiration within the writings of German thinker Martin Heidegger, who believed that dwellings present a way of each shelter and self-expression. Architects thus design environments that imbue life with which means, he argued.

Social scientists are beginning to be part of architects in interested by how the constructed surroundings can have an effect on loneliness. In his latest public well being advisory, Surgeon Basic Murthy outlined six pillars to advance social connection. Within the first pillar, he really helpful facilitating connection amongst folks by means of higher city planning, resembling offering folks with quick access to inexperienced areas and bolstering the attain of public transit.

Equally, in January, a cross-disciplinary group of researchers in Australia and England, whose areas of experience embrace city planning, public well being and sociology, recognized a number of city design options which have the potential to scale back loneliness. These options embrace frequent areas, walkability, public transit, housing design, sense of security and entry to pure areas.

Whereas the main focus of such city design tasks usually intention to get folks collectively, there may be rising consciousness that connecting folks with the pure world might also alleviate loneliness. “Individuals could be socially remoted however nonetheless not really feel lonely,” says Emily Rugel, an environmental epidemiologist on the College of Sydney. “They could discover that skill to faucet a biophilic connection and exit and look at wildlife and stroll among the many timber. [That may be] sufficient to make them really feel linked to the broader world. They don’t essentially want interplay with associates or members of the family to try this.”

Contemplate, as an illustration, a small venture in New Zealand that goals to alleviate loneliness, partially, by serving to folks reconnect to their prolonged households and ancestral lands. Members of 1 Māori subtribe, the Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, developed a 30-home papakāinga, a kind of communal Māori cohousing setup, on ancestral land. Accomplished in 2016, that venture introduced folks collectively by connecting houses through shared lanes, neighborhood gardens and play areas for youngsters.

Builders wished folks to really feel as in the event that they have been strolling the identical paths as their ancestors, researchers wrote within the 2022 difficulty of Wellbeing, Area and Society. They hoped that feeling would assist residents really feel rooted of their tradition and the lengthy arc of time. Even when constructing on ancestral lands just isn’t doable, bringing usually far-flung neighborhood members again collectively has the potential to revive languages and cultural practices, the authors observe. However extra analysis is required to know if a return to the papakāinga reduces loneliness.

The underside line is that increasing how we take into consideration loneliness has the potential to broaden the toolkit of doable interventions, Parsons says. “We will regulate our loneliness by not essentially calling up a buddy however by going out, going for a stroll, or going to the library, or going and sitting in a espresso store.”

Loneliness and local weather change

A few years in the past, I moved to a small metropolis in New England whereas a number of months pregnant. I knew nobody besides my husband and spent my lonely days wandering the woods behind my home. As soon as, after my child was born, I strapped him right into a service and scrambled down a steep embankment. There, on the fringe of a lake, a log had lodged into the rocky shore. We’d spend hours watching waves pummel the log’s tough bark. As I noticed loons dive for fish in summer season and heard waves shatter ice like glass in winter, my loneliness would briefly ebb.

I used to be reminded of this log after talking with Sarah Wright about songspirals and why we must always all domesticate intentional relationships with the pure world. I had by no means thought of my relationship with the log significantly vital, and even as a relationship in any respect. However Wright made me notice that on this new and unfamiliar place, the log had offered a haven. Her phrases additionally defined the disappointment I felt through the years because the waves chipped away the log’s bark — a course of accelerated little doubt by a lake that froze over much less and fewer come winter.

There’s a phrase to explain what I used to be feeling. Within the early 2000s, environmental thinker Glenn Albrecht of the College of Sydney coined the time period “solastalgia” to explain the ache or illness an individual experiences when pure or human-made disasters destroy their house. Etymologically, the phrase originates from each solace and desolation. Desolation, Albrecht wrote in 2007, has “meanings linked to abandonment and loneliness.” Solastalgia can be a play on nostalgia.

Albrecht felt compelled to create such a time period after observing and interviewing over 50 folks dwelling within the Hunter Valley area north of Sydney, the place there was intensive mining. Residents expressed considerations over how mining was affecting their well being and well-being. “The truth that you possibly can see these big mine heaps et cetera makes you suppose that someday sooner or later there could also be dreadful penalties for the water desk motion within the valley,” a person named Leo stated. A lady named Eve stated, “When the coal is gone, the folks of Singleton shall be left with nothing however ‘the ultimate void.’ ”

The residents’ expertise is ironic, Albrecht famous. These individuals are descended from the colonizers who dispossessed Indigenous communities of their land. Now, this “second wave of colonization,” Albrecht wrote, “is main to finish dispossession for some and solastalgia for these left behind.” In different phrases: desolation, abandonment and loneliness.

In recent times, associated phrases have emerged: ecoanxiety and local weather grief (SN: 2/29/20, p. 22). In contrast to solastalgia, although, researchers hardly ever join these concepts to loneliness. That’s altering. In 2022, a web-based survey of over 3,000 German adults, as an illustration, confirmed that those that scored excessive in loneliness on the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale additionally tended to attain excessive in local weather anxiousness on a distinct scale.

These phrases clarify that constructing a relationship with the nonhuman parts of our world is bittersweet on this time of fast local weather change. We come to like what we might effectively lose. But, absent these deep relationships, how can we look after the world we reside in?

Final winter in my New England city, it didn’t snow till mid-February and the water across the log by no means froze. These months of battering waves have been laborious on the log. After I trekked right down to that rocky shore one muddy spring day, my two school-aged youngsters in tow, the log was clean to the contact and white as bone.

On a solo stroll a couple of weeks later, I found that the log was gone. It had, after so a few years of holding on, floated away.