Giant viruses are known to try out a variety of different sly tricks.

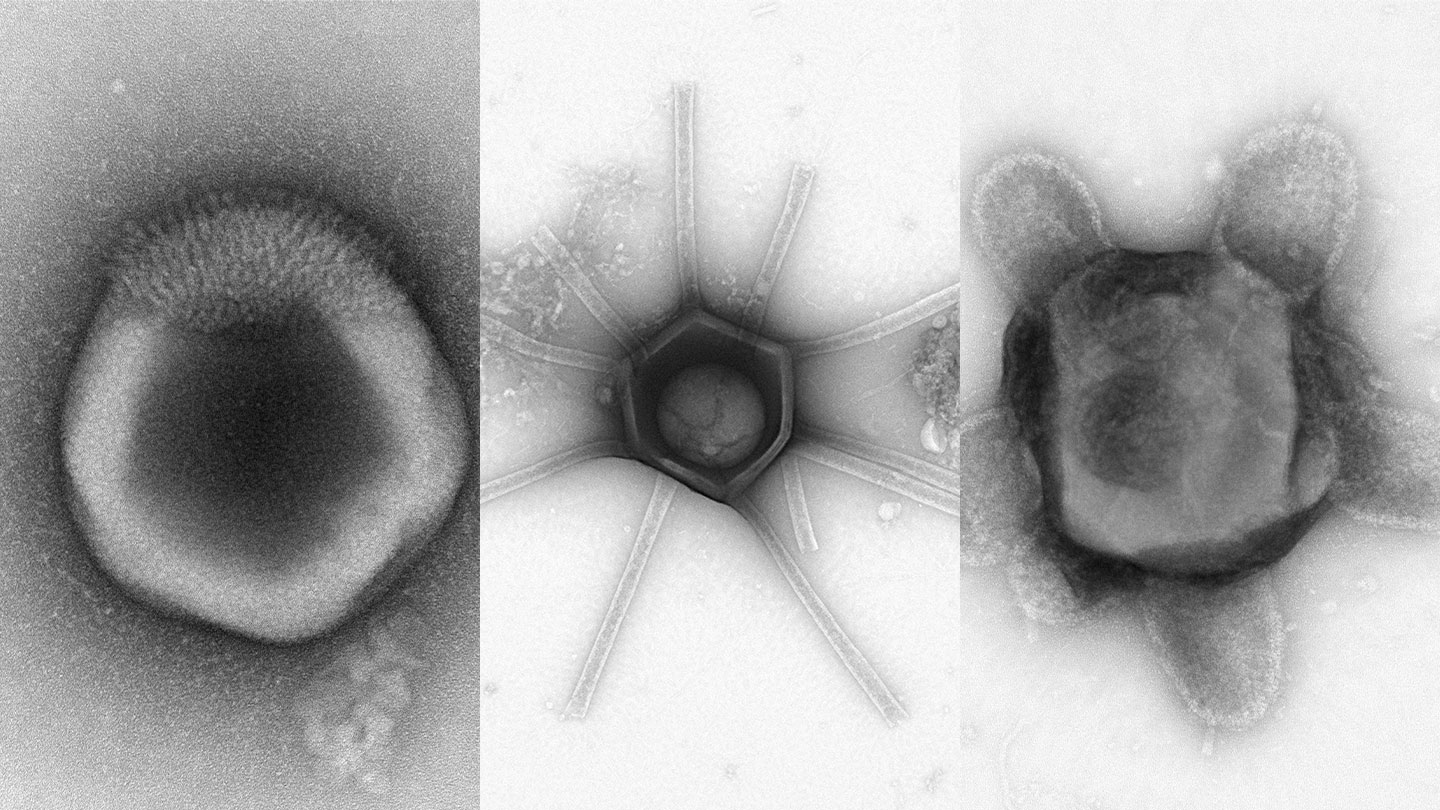

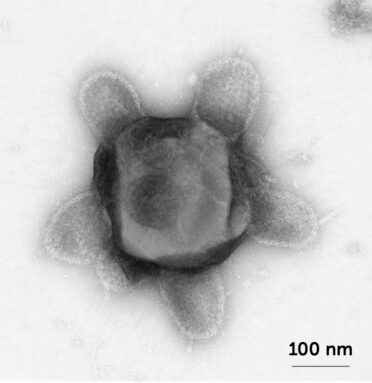

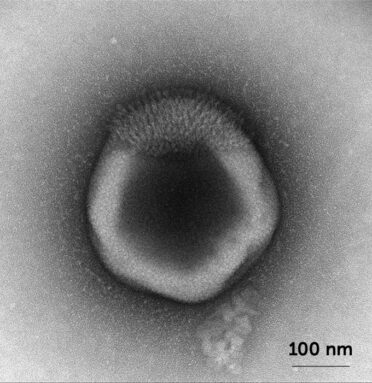

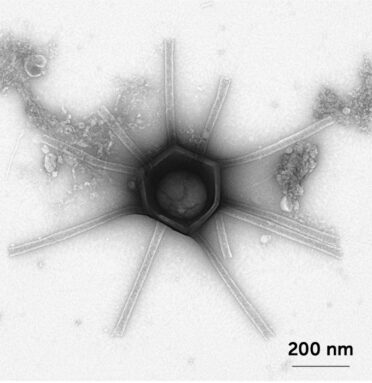

New images reveal new information varied — and sometimes whimsical — shapesHundreds of giant soil-dwelling viruses are possible. One shape is dubbed “haircut” for its fibers that bristle like freshly buzzed hair. “Gorgon” has tubelike appendages snaking from its shell. And flaps poking out of “turtle” resemble the reptile’s head, limbs and tail, virologist Matthias Fischer and colleagues report June 30 at bioRxiv.org.

These and other peculiar-looking shapes “clearly tell us that we’ve underestimated how structurally diverse these viruses are,” says Fischer, of the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, Germany.

Then, there is the The first giant virus was discovered in 2003Scientists collecting genetic material in the environment have discovered an entire world of giant viruses.SN: 3/21/18). These viruses have an average diameter 10-50 times greater than the virus that causes the common cold. Genetic data suggests that giant viruses are widespread, diverse and numerous.

But genetics can’t tell us everything about a virus’s biology, says Steven Wilhelm, a microbiologist at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. “We don’t know what we’re looking at, who it infects or what it could possibly be doing.”

Fischer says that his new work may help to change that. Using transmission electron microscopy, his team analyzed about half a kilogram of soil from Harvard Forest in Petersham, Mass., to produce an image gallery of giant virus diversity — potentially.

Fischer is careful not to call the virus look-alikes “viruses” just yet. The researchers have seen the particles only with a microscope; they haven’t confirmed that the potential viruses can infect particular organisms.

Still, looking at the structures Fischer’s team identified, microbiologist Frederik Schulz of the Joint Genome Institute in Berkeley, Calif., says he’s “convinced that many of these are actual virus particles.”

Scientists are only able to speculate as to why giant viruses could form tube-shaped, bristly, or turtle-like appendages. Fischer says they could help a virus spread through the environment or even infect a new host. “It’s going to be a wild ride … to see what each of these structures do.”

Fischer believes that even more bizarre shapes are yet to be discovered. “If a handful of forest soil already contains so many different virus particles,” he says, “this is clearly just the very tip of the viral Mount Everest.”