Magnificent as they’re, most fossils are somewhat monochromatic, prompting paleontologists to go to nice lengths to deduce what colour these historical organisms might need been.

Some distinctive fossils have preserved the pigment molecules in dinosaur feathers and scaly pores and skin. However given the hundreds of thousands of years that separate us from the lives of these historical animals, scientists aren’t completely certain how the method of fossilization might need meddled with these chemical imprints.

To take a number of the guesswork out of imagining the colours of fossilized creatures, a staff of researchers from China and Eire has run a collection of lab experiments to affix the dots between the tonal patterns usually seen on fossilized bugs and the properties of the unique tissue, to verify the true nature of their coloration.

“Many fossil bugs present monochromatic colour patterns which will present helpful insights into historical insect conduct and ecology,” Nanjing College paleontologist Shengyu Wang and colleagues write of their printed paper.

“Whether or not these patterns mirror unique pigmentary coloration is, nevertheless, unknown, and their formation mechanism has not been investigated.”

Fossilized bugs usually show blackish-brown spots, stripes, or blotches – patterns which may, the researchers hypothesized, mirror the thickness and hardening of insect exoskeletons or the pigment content material of these tissues.

Whereas such tonal patterns might not rival the dazzling colours of iridescent bugs preserved in amber, the patterns may nonetheless signify necessary clues on insect appearances.

Utilizing gentle and scanning electron microscopy, the researchers imaged a fossilized orthopteran identified for having putting monochromatic patterns on its wings, akin to the modern-day banded-wing grasshopper. Solely at midnight bands did they discover traces of the insect’s exoskeleton.

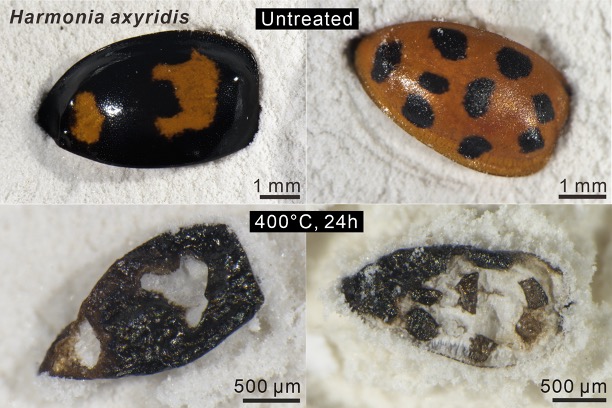

Subsequent, Wang and colleagues chosen three present-day beetle species with easy patterning, wrapped their exoskeletons in aluminum foil, and baked them at temperatures between 200 °C and 500 °C to simulate fossilization.

Inspecting the specimens utilizing scanning electron microscopy, the researchers discovered the darkish patches that remained have been certainly from the pigmented elements of the exoskeleton, wealthy in melanin. These spots resisted warmth degradation whereas melanin-poor areas have been misplaced, as you may see within the picture under.

Considerably unusually, the heated specimens went by an middleman section of degradation the place they turned black throughout earlier than revealing their patterns as soon as extra.

The outcomes recommend that if a specimen’s darkish hues are uniform, it would simply be an artifact of fossilization. Striped or blotchy patterns, nevertheless, may very well be thought-about consultant of the fossilized bugs’ unique colour palette, the researchers conclude.

Chemical proof of melanin has been discovered earlier than, within the dark-colored exoskeleton stays of different fossil bugs, together with a beetle, wasp, and damselfly.

However regardless of bugs’ nice abundance, and a fossil report that stretches again to the Early Devonian interval, some 400 million years in the past – when the primary vascular vegetation have been simply getting a foothold – the coloration of fossilized bugs has been largely ignored in comparison with vertebrates.

Wang and colleagues say their experimental examine “opens new avenues” for decoding insect fossils, now that now we have a greater concept of how bugs are preserved.

“Our knowledge signify the primary empirical proof that the monochromatic patterns in compression fossils of bugs are organic in origin and signify melanin-based colour patterns,” Wang and colleagues write.

Given what we have come to grasp about how evolution favors sure colours, they hope future research evaluating their tonal patterns by deep time may “yield helpful insights into the purposeful evolution of insect coloration, conduct and physiology in historical ecosystems.”

The examine has been printed in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Organic Sciences.