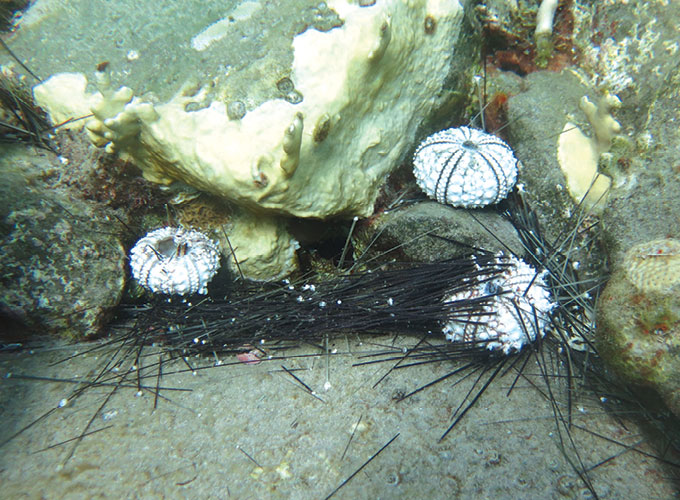

Once bustling with over 5,000 long spined sea urchins the coral reef became a ghost village in just a few days. Near Saba in the Dutch Caribbean, white skeletons and dangling spines littered the reef. The water was cloudy from the remains of disintegrating corpses. Half of the urchins were gone in a matter of weeks last April. Diadema antillarum, in a section of reef called “Diadema City” had died. Only 100 were left in June.

The mysterious death wave began in February across the Caribbean. It’s eerily similar to a mass mortality event in 1983 that wiped out as much as 99 percent of the Caribbean Diadema population — a huge blow to not only the urchins, which have not fully recovered four decades later, but also the reefs. Algae can overtake a reef without urchins, causing damage to adult corals and leaving no place for new coral to grow.

Before the die-off, Saba’s coral cover — the part of a reef that consists of live hard coral rather than sponges, algae or other organisms — hovered around 50 percent. Today, it is just 3%.

“It’s just downhill, downhill, downhill,” says Alwin Hylkema, a marine ecologist at Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences and Wageningen University in the Netherlands who is based in Saba (pronounced “say-bah”).

I learned about Saba’s sea urchin problem only shortly after I learned that the island existed. Saba is a blip in the Caribbean; at 13 square kilometers, it’s about a quarter the size of Manhattan, with the towering Mount Scenery volcano at its center. Its reefs attract scuba divers, but a lack of beaches shields it from regular Caribbean tourist traffic — hence its nickname, “the unspoiled queen.” What the island lacks in size and sand it makes up for with its great variety of species, its biodiversity. Steep cliffs support several microclimates. A visitor can easily hike in a matter of hours from volcanic rock to grassy fields to misty cloud forests.

This diversity makes Saba the perfect spot for Sea & Learn, an annual educational program that brings scientists from around the world to the island. Lynn Costenaro, a former owner of a dive shop, started the program to encourage more divers from Saba to visit during off-season. But the event has grown to play an important role in educating the island’s 2,000 residents about their home’s unique wildlife and ecosystems.

The scientists will be presenting their research in restaurants and plazas throughout October on everything from biology to geology to astronomy. Many researchers host public research trips on the shore and underwater, where people can view stars, rock formations, lobsters, etc.

This type of local engagement with nature comes at a moment when many species are in danger, not just on Saba. Although islands cover only about 7 percent of the world’s landmass, they are home to an estimated 20 percent of all species — and 75 percent of all documented extinctions.

Some island species only inhabit one island while others spread across many islands in small groups. Smaller populations of species may develop very narrow adaptations specific to an island, which can cause problems when people and other invasive species arrive. Today, any plant or animal found on an island can be identified as such. Twelve times as likely as species found on the mainland to become extinctThe November 2021 issue of the Irl featured a report by an international group and Irl. Global Ecology and Conservation. The decline is increasing at an alarming rate. As biodiversity decreases, islands are less complex and more vulnerable to disruptions such as climate change.

“We’re in the midst of a biodiversity crisis … and islands are really bearing the brunt of that global change,” says arachnologist Lauren Esposito of the California Academy of Sciences, who has The presented research on spiders and scorpions at Sea & Learn.

The features that put island inhabitants at risk — their small size and isolation — also make them wonderful laboratories. Like the famous Galápagos Islands that turned Charles Darwin on to natural selection, islands present opportunities to study individual species as well as ecosystem dynamics, in a relatively small microcosm. The California Academy of Sciences launched Islands 2030 in 2021. Esposito was co-lead. It is located in five archipelagos tropical, including Saba’s Lesser Antilles. The program aims to conduct biodiversity studies and to train local communities as guardians of the environment. The program took its inaugural trip to Saba’s Sea & Learn last October.

I attended that Sea & Learn and tagged along on field trips to see what progress and pitfalls researchers had experienced while working on Saba to protect a tiny orchid, a bright-billed bird and those dying urchins.

Counting orchids

On my first night, I joined locals and tourists at the Brigadoon restaurant to hear Mike Bechtold talk about Saba’s orchids. Bechtold is a retired nuclear weapons expert from Virginia, who first visited the island in 2003 to learn about the orchids. He’s since presented several times at Sea & Learn. He presented for the first time in seven years.

Bechtold defined an orchid as a flowering plant that has three petals and a list of unusual characteristics. described the chaotic history of orchid research in SabaThere have been a number of miscommunications which has led to count discrepancies. Bechtold, however, counts 32 species in a recently published book.

“To know what we have to preserve, well, we at least have to know what is there,” says Michiel Boeken, a former secondary school teacher from the Netherlands who studied orchids on Saba during his 2010 to 2012 tenure as principal of the island’s only secondary school.

Bechtold led an orchid-hunting hike to Spring Bay the morning following his presentation. We walked along the island’s only major road — aptly named The Road. We descended into a forest of trees that were covered in mosses and other plant life from the trailhead. We’d only walked for about 10 minutes when Bechtold pointed out an Epidendrum ciliareThe most common Saba orchid, pictured perched on a tree.

We carefully walked over the hermit crabs and looked for the piles of rocks marking where to go to find another species. Brassavola cucullata. Bechtold, Boeken and colleagues had surveyed the Spring Bay population from 2011 to 2014 to see if Saba’s numbers were declining. We finally spotted the tiny yellow and white flowers of the Spring Bay as we began to descend the steep hillside. B. cucullataAtop a tall tree, with a metal tag attached beneath it. It was #582 out of 834 B. cucullata Bechtold helped tag plants a decade ago.

We counted the plant’s leaves and measured them. Bechtold’s team had found that larger plants with more leaves had a better chance of survival than smaller plants, as did plants that were higher off the ground, like #582. Wild goats often eat plants that are close to the ground.

It is found in Mexico and northern South America. Here, however, The B. cucullataIn fact, the population was actually decliningThe researchers found that small plants were dying rapidly and new plants weren’t starting to grow. This was reported by the researchers in 2020. International Journal of Plant Sciences. Without counting flowers for many more years, if not decades, it will be hard to know if the decline reflects natural population dynamics or if it’s a troublesome trend.

Regardless of cause, the population’s small size makes the island’s B. cucullata vulnerable. A recent hurricane swept away large orchid plants from trumpet trees. Some of the orchid plants were crushed while others were left to die from goat chewing after their tree fell.

Red-billed tropicbirds being tracked

A week after the orchid hike, I found myself perched on a boulder high up on a cliff at Tent Bay on the island’s southern coast, looking for nests tucked into narrow rock crevices. Lara Mielke (German ecologist), another volunteer, and I set out early in the morning to beat the heat. We climbed hand-over-foot up the hill. Red-billed tropicbirds with long white tails swooped overhead, their bright crimson beaks shining out over the ocean.

Around 1,500 breeding couples Phaethon mesonauta aethereus, one of the three subspecies of red-billed tropicbirds, breed on Saba, as much as a quarter of the subspecies’s global population. Tropicbirds spend most of their lives at sea, only coming to land for a few months each year to breed and raise a single chick. Their cliffside nesting spot makes the birds hard to study even when they’re on land. Fortunately, on Saba and the neighboring island Saint Eustatius, or “Statia,” the terrain is tough but not impossible to scale.

As I was climbing, I was surprised by the abrasive squawk that came from a deep crevice where a nest was hidden. The birds are more squawky than they bite. Mielke was able reach her arm into the tiny opening to extract the bird and wrap a band around it’s leg.

This bird is vulnerable to invasive predators due to its tameness. Tropicbird chicks are often eaten by feral cats that roam the island’s cliffs. Saba Conservation Foundation established cat eradication programmes with mixed success over the years.

After banding the bird, Mielke handed me a warm egg she’d pulled from the nest. As she filled a plastic bag with water, I took the egg and held it in my hands. An egg’s buoyancy indicates how far along it is. We knew, though, that once the chick hatched, it probably wouldn’t live long. Researchers have seen the disappearances of all the chicks at Tent Bay in the past, possibly because they were taken by feral cats.

On the other side, Chicks have better odds. In 2011 and 2012, Boeken — involved in several conservation efforts on Saba — The hatchlings of 62 of the 83 eggs were found to be healthy, which is 75 percent.Old Booby Hill, near Spring Bay to its north, was the only place where the chicks survived to build their nest. And on Statia, which has no cat problem, as many as 90 percent of chicks survive after they’ve hatched. Despite this, it is not known why. Their colonies produce fewer chicks Because many eggs never hatch.

Tropicbirds are faithful to both their mate and nest site, sometimes even returning to the same rock cavity each year, says ecologist Hannah Madden of the Caribbean Netherlands Science Institute, who moved from the Netherlands to Statia in 2006 and has spearheaded Statia and Saba’s tropicbird research. However, the birds might be loyal to a fault. Relocating or finding a new partner may increase the chances of successful chick-raising success if a nest is repeatedly broken into or eggs are not hatched.

Madden and Mielke, working as an independent researcher, are now analyzing GPS data of the subspecies’s foraging patterns. The Caribbean’s last assessment of seabirds It happened more than two decades ago, so Madden has been hosting webinars to teach people on other islands how to collect such data during next year’s nesting season.

“In 2023, we want people from as many islands as possible in the Caribbean to get out there and monitor the seabirds on their islands,” she says.

Hitting home

Peter Johnson is a Saba resident from the 11th generation who teaches mathematics and physical science at the secondary school. He often sits outside after classes to listen to the red-billed tropicalbirds fly overhead.

“Their birdcall is so unique,” he says. “They’re certainly something that reminds me of home.”

Johnson was a kid when Sea & Learn started in 2003. He can still remember the day in fifth grade that scientists came to his school and allowed him to try on a spelunking headgear for cave exploration. He returned to Saba many years later after completing engineering degrees in Virginia. “You’re more inclined to be proud of where you’re from, the more you know about it,” he says.

Esposito, who is part of the Islands 2030 initiative recalls being impressed at the natural language Saban youth use when discussing nature. Sea & Learn scientists visit Saba’s schools to teach about the island’s unique species. When Esposito asks students if they’ve seen the island’s local snake — its only snake, the red-bellied racer — they usually say yes. She doesn’t get the same answer on Statia or neighboring islands.

“I have seen the direct effect of Sea & Learn,” she says. “There is this connection between the people coming to do research and the local population and communities that doesn’t exist in most other places.”

Sea & Learn coordinator Emily Malsack hopes the program encourages locals to stay on Saba to work in conservation. It’s already having an impact. Johnson is now president of Saba Conservation Foundation. Dahlia HassellKnijff is a Saban native. She earned her biology degree from Mississippi and returned to Saba to oversee projects at the Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance. She also grew up attending Sea & Learn.

“It was a very tiny organization [at the time], but it didn’t seem tiny to me,” Hassell-Knijff says. “It was like a dream come true for a little kid.”

Hassell-Knijff’s story is “an indication of progress that’s to come,” Esposito says. Islands 2030 will recruit scientists from five archipelagoes in order to send them to the California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco. They can pursue an advanced degree and join a group of scientists from their archipelago. It is hoped that the next generation will return home to lead biodiversity conservation and science.

There’s a need for this support. Researchers who study island biology often travel abroad to spend some time, then leave. This causes research to stop and disrupts long-term studies that are vital to understanding trends in population of, for example, orchids or tropicbirds. Mielke just finished her six-month stint on Saba to go home to Germany. Madden returned to the Netherlands after 16 years of living on Statia.

“It’s just tough,” Madden says. “At this point, I don’t know who will take over the projects that I’m working on.” Bechtold, too, worries about who will track the orchids after he and Boeken retire from research and can no longer travel to Saba.

The urchins are being saved

Alwin Hylkema was a marine ecologist. He presented his research on DiademaThe plaza was crowded with more than 100 children and adults. Hylkema has become a local star. He began his research on urchins in the Netherlands from his home. After a while, he visited Saba twice a calendar year. Then he realized it was better to study his findings on Saba. He and his family moved to Saba in 2019.

Hylkema began to work on restoration since then. DiademaSaba’s coral reefs. But it’s a challenge: After urchin larvae settle onto a reef, they are easily eaten by queen triggerfish and spiny lobsters. To help more of the animals survive to adulthood, Hylkema’s team has been collecting the youngsters, known as settlers, and growing them in a lab on Saba. Once they reach a certain size and are less likely be eaten, the team releases them back to the reefs.

Things started to improve for animals in October 2021. The same week saw the release of the first calf. Hylkema’s team bred DiademaFirst time in Caribbean history that a captive was held.

It was just the right time for lab-grown Urchin success. Hylkema hopes to produce 1,000-2,000 juveniles by the end this year. These will be used to replenish the Diadema City population. However, this will not be possible until the cause of the death has passed. Cornell University researchers are analysing DiademaHylkema sent tissue and other materials to establish the cause.

One afternoon, I hitchhiked south from the town of Windwardside in the middle of the island to the harbor in Fort Bay, where Hylkema’s lab is located. I wanted to see the captive-bred animals. Diadema. The lab’s crates were arranged by size. The youngest looked like inch-long Pom-poms, while the older ones looked more like plums with long, black sewing needles.

The urchin larvae are kept in an enclosed storage container at the back. They then move around in glass jars and on a vibrating plate. After about 50 days, the larvae should settle down and be transferred into the crates. If all goes well, the animals will grow in the lab until they’re big enough to be taken out to the reefs, where they’ll begin the next generation of Diadema.